insights

Dina Management Limited v County Government of Mombasa & 5 others (Petition 8 (E010) of 2021) [2023] KESC 30 (KLR)

Background of facts

The first respondent, the County Government of Mombasa, was accused by the appellant, Dina Management Limited, of forcibly entering the suit property registered to them on several times in September 2017 without giving prior notice and further demolishing the perimeter wall facing the beach. The first respondent argued that since the suit property was public land rather than private, the entrance and demolition were an enforcement action intended to construct a highway to the beach.

Earlier on a lawsuit had been filed cited as Elizabeth Karangari Githunguri v. Dina Management Limited, HCCC No. 131 of 2011 which was decided in favor of the appellant. The appellant argued that this case resolved the questions of who owned the suit property, and whether there was a public road through the suit property.

The appellant filed a petition against the first respondent, seeking declarations of violation of its rights under Kenya’s Constitution and a permanent injunction to prevent interference with the suit property. The first respondent also filed a separate petition, asserting that the property was public land and the subsequent acquisition was void.

Trial court’s findings:

The trial Court held that:

- There was an access road through the open space to the sea, which was later blocked by the suit property’s allotment;

- The first respondent acted within the law in removing the wall which blocked the access road;

- The first respondent’s suit was not res judicata;

- The first respondent’s suit was not time barred as it related to constitutional violations of a continuing nature; and

- The appellant could not be protected as an innocent purchaser without notice.

The appellant was dissatisfied and they filed an appeal in the Court of Appeal. The appellate Court dismissed the appeal and a cross appeal filed by some of the Respondents and upheld the trial court’s decision. Aggrieved, the appellant filed the instant appeal.

ISSUES FOR DETERMINATION

- Whether the right to property (art 40 C.O.K) extended to property which was unlawfully acquired;

- Whether being in possession of the instrument of title was sufficient proof of ownership of land where the registered proprietor’s root title was under challenge.

- What was the procedure for the allocation of un-alienated land?

- What were the factors to consider in determining what amounted to an intergovernmental dispute?

- What were the limits of the Supreme Court’s jurisdiction under article 163(4)(a) of the Constitution on appeals as of right in a matter involving the interpretation or application of the Constitution?

- Whether the Supreme Court had the jurisdiction to determine an issue which was not articulated at the trial court but only at the appellate court.

- What was the nature of the doctrine of res judicata?

- What were the elements to be proven before a court could determine that a matter was res judicata?

- Whether decisions made by courts of concurrent jurisdiction made in rem were binding on courts of equal jurisdiction.

At the Supreme court appeal, not all the grounds set out by the appellant satisfied the court’s jurisdictional threshold under article 163(4)(a) of the Constitution. The appeal correctly invoked the court’s jurisdiction to the extent of determining only three questions:

- Whether the appellant’s rights under article 27(1) and 50 (1) of the Constitution were violated by the court’s application of the doctrine of res judicata or in the alternative, issue estoppel;

- Whether the appellate court’s interpretation of bona fide purchaser amounted to a violation of the appellant’s right to property under article 40 of the Constitution;

- Whether the suit amounted to an inter-governmental dispute under article 189(3) of the Constitution, and the Inter-governmental relations Act.

HOLDING

The Supreme Court held as follows:

- Whether the appellant’s rights under article 27(1) and 50(1) of the Constitution were violated by the court’s application of the doctrine of res judicata or in the alternative issue estoppel;

The theory of res judicata is based on public policy and aims to ensure that litigation is objective and that individuals are not harassed again for the same case. Estoppel can be used to assert the doctrine of res judicata, which states that once a judgment is rendered, subsequent processes are barred. If res judicata was pleaded as an estoppel to an entire cause of action, rather than a specific issue, it implied that the earlier judgment resolved all legal rights and obligations of the parties, including questions of law and factual findings. This was a type of action estoppel. Res judicata was included in section 7 of the Civil Procedure Act.

HCCC No. 131 of 2011 did not significantly address the issues raised in ELC Petition 12 of 2017. The court’s findings in HCCC No. 131 of 2011 were inconclusive due to the unavailability of State organs, specifically the Registrar of Titles, to make a determination. The second to sixth respondents were not parties in the case. The parties in ELC Petition 12 of 2017 differed from those in HCCC No. 131 of 2011, with the exception of the appellant. Therefore, ELC Petition 12 of 2017 was not res judicata since the necessary components were not met. The appellant’s constitutional rights to equal protection under Article 27(1) and fair hearing under Article 50(1) were not breached by the appellate court’s interpretation of res judicata in this case.

b. Whether the appellate court’s interpretation of bona fide purchaser amounted to a violation of the appellant’s right to property under article 40 of the Constitution.

Article 40(6) limited the right to property as not extending them to any property that had been found to have been unlawfully acquired hence appellant’s title was not protected under article 40 the Constitution and the suit property, by its very nature being a beach property, was always bound to be attractive and lucrative. The appellant ought to have been more cautious in undertaking its due diligence. Moreover, the root of the title having been challenged, the appellant could not benefit from the doctrine of bona fide purchaser. The registered proprietor in order to prove ownership ought to prove the legitimacy of their root title to show that it is legal, formal and free of encumbrances, including unregistered interests, beyond the instrument of title as proof of ownership.

c. Whether the suit amounted to an inter-governmental dispute under article 189(3) of the Constitution, and the Inter-Governmental Relations Act.

The court determined that the main question was whether the suit property was owned by the County Government or the National Government, rather than a dispute between the two. The suit property was fundamental to the conflict, leading to the combination of Petition 8 of 2017 and Petition 12 of 2017. The intergovernmental nature of the debate was secondary to the main issue at hand. The fact that the first respondent initiated separate proceedings in response to the appellants did not modify the character of the proceedings. The suit property’s ownership concerns and challenges would have been addressed in response to the petition, even if by way of cross-petition.

CONCLUSION

The hearing of the appeal and its subsequent dismissal raised critical considerations that parties should take into account when acquiring property. They are as follows:

- Where the registered proprietor’s root title is under challenge, the registered proprietor must prove the legality of the title and show that the acquisition was legal, formal and free from any encumbrance;

- Proprietors should ensure that if the property being acquired was initially unalienated Government Land, the correct procedure for allocation was followed;

- If the 1st registered owner of a property did not acquire property regularly, the ownership of such property cannot be protected under article 40 of the Constitution and such a party cannot benefit from the doctrine of bonafide purchaser.

The Property and Conveyancing team is always available to provide more insight on the implication of this case to due diligence investigation prior to property acquisition. Should you have any queries or need clarifications on the contents of this alert, please contact us via info@agoadvocates.com.

SECTIONAL PROPERTIES ACT 2020

INTRODUCTION

The Sectional Properties Act came into effect in December, 2020 in alignment with the provisions of the Constitution of Kenya 2010, the Land Act No. 6 of 2012, the Land Registration Act No. 3 of 2012 and the National Land Commission Act No. 5 of 2012.This Act repealed the Sectional Properties Act of 1987.

The Act creates individual title for apartments, maisonettes, flats, and seeks to divide buildings into units to be owned by individual unit owners.

The Act also seeks to simplify the process of registration of sectional properties and create an enabling environment for investors and property owners. Therefore, it seeks to guarantee the rights of property owners by conferring absolute rights to individual unit owners over their units.

The Act does not recognize the concept of reversionary interest therefore it motivate lenders and financiers to offer credit facilities to the individual unit owners as they may now charge the individual units directly without requiring the consent of the developer and or the manager.

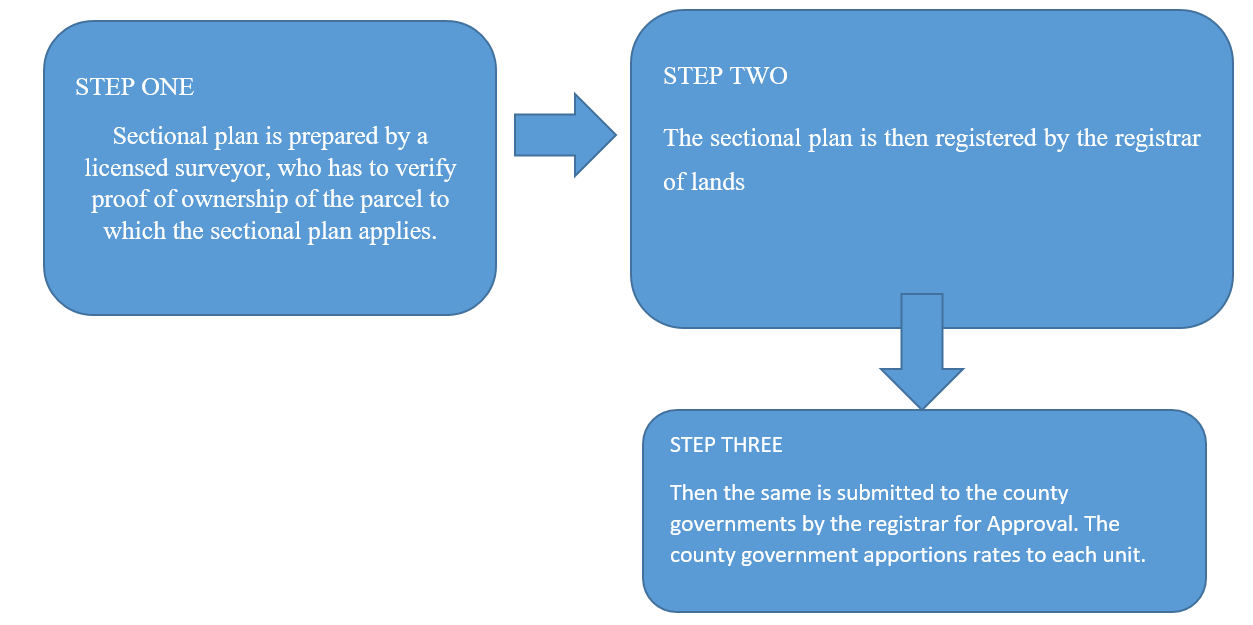

CONTENT OF SECTIONAL PLAN

Section 9 of the Act provides for the content of a sectional plan and requires that all sectional plans must describe at least 2 units and must be:

- Geo-referenced;

- indicate the parcel number;

- indicate unit numbers;

- indicate approximate floor area of each unit;

- be signed by the proprietor;

- be signed and sealed by the Director of Survey; and

- clearly indicate the user of the unit.

Once a sectional plan is registered, the registrar is required to close the register of the parcel described in it and open a separate register for each unit.

The register for each unit will contain;

- description of the unit

- share apportioned to the unit owner in the corporation

- any encumbrances attached

Each unit should be issued with a certificate of title (freehold property) or certificate of lease (leasehold property), and the title shall include each unit’s proportionate share in the common property.

SALIENT FEATURES OF SECTIONAL PROPERTIES ACT, 2020

- THE CORPORATION

The Sectional Properties Act provides that upon registration of a sectional plan, a corporation is formed automatically and the registrar of Lands shall issue a Certificate of Registration in respect of the Corporation.

Under Section 17(2), a corporation shall consist of all persons who are owners of units in the parcel to which the sectional plans relates.

According to Section 17(6) of the Act, the provisions of the Companies Act do not apply to Corporations. The Corporation carries out the duties imposed upon it by the by laws. Dispute in relation to contraventions of the by-laws are referred to the committee which is an internal dispute resolution mechanism of the corporation and without any prescribed limits as to the penalties to be levied.

If a party is aggrieved with the decision of the committee, the party can do an appeal to the Environment and Land Court (ELC) against the decision of the committee.

The Corporation has wide-ranging duties & powers including:

- Keeping the common property in a state of good repair.

- Controlling, managing and administering the common property.

- Establishing and maintaining a fund for administrative expenses.

- Effecting insurance and payment of premiums.

- Constitute an internal dispute resolution committee on a need basis.

- OWNERSHIP

The Sectional properties Act applies to land held in both lease hold tenure and free hold tenure where the intention is to confer ownership.

The new law has reduced the unexpired leasehold period to 21years from the 45 years required under the repealed law. This enlarges the purview of the sectional properties laws to extend to proprietors of all long term leaseholds which are defined in law as leases for a period of twenty-one years and above.

- CONVERSION OF SUBLEASES

The process of conversion may be commenced by the developers, the management company or the individual unit owner. If the developer is unwilling to surrender the mother title for purposes of the conversion, the registrar may register a restriction against the title to prevent any further dealings on it.

The process of conversion of subleases to sectional unit titles entails submission of:

- Sectional plan;

- Original title;

- Long term lease previously registered; and

- Rent apportionment for the unit where applicable.

Section 13 of the Act provides that all long term sub-leases that are intended to confer ownership of apartments, flats, maisonettes, town houses or offices that were registered before the commencement of this Act shall be reviewed to conform with section 54 (5) of the Land Registration Act. This shall be done within a period of two (2) years of the commencement to the Act. Which means on or before 28th December, 2022.

This will not entail starting a transaction from scratch and an owner who has already paid stamp duty in respect of the said sub-leases shall not be required to pay stamp duty during the revision.

CONCLUSION

From the above discussion, it is evident that the Act has greatly impacted the state of real estate ownership by introducing the aspect of ownership of sectional units in buildings by individual unit owners. This has greatly addressed the challenging and outdated provisions on land set out in the Repealed Act. It is a positive and progressive step towards the development of land law regime in Kenya.

LAND TITLE CONVERSION OF OLD REFERENCE NUMBERS TO NEW PARCEL NUMBERS

Background

The Cabinet Secretary, Ministry of Lands and Physical Planning vide a Special Gazette Notice No. 11348 of 2020 (“the Notice”) published on the 31st December, 2020 and a Press Statement on the 12th of January, 2021 notified the general public that the ministry had embarked on the process of conversion of old land reference numbers to new parcel numbers.

What is the purpose of the conversion process?

Before the enactment of the Land Registration Act 2012, the registration of title to land in Kenya was characterized by multiple statutes, namely, the Government Lands Act (GLA), the Titles Act (LTA), the Registration of Titles Act (RTA) and the Registered Land Act (RLA).

This regime not only led to inconsistent conveyancing practices which were often ineffective but it also led to the duplicity of titles and fraudulent dealings in property. The enactment of the Land Registration Act 2012 sought to streamline these issues by repealing all the laws under the previous regime and giving rise to a consolidated system of land registration under the Land Registration Act.

However, registration under the Act is yet to be effectively implemented with only the savings and transitional provisions of the Act being in use. This means that the country’s land regime continues suffer the problems created by the previous regime even with the existence of a new regime.

Who shall be affected by the conversion process?

Anyone who owns property under the previous land regime shall be subject to the conversion process. The initial piloting phase of the process is to be carried out for titles within Nairobi.

What is the legal basis of the conversion?

As outlined above, the conversion process is couched under the Land Registration Act, 2012 (“the Act”) and the Land Registration (Registration Units) Order of 2017 (“the Regulations”) which were enacted by Parliament pursuant to Article 68 of the Constitution which requires Parliament to revise, consolidate and rationalize existing land laws. Additionally, Section 6 of the Act gives the Cabinet Secretary powers to constitute an area or areas of land to be a land registration unit and may at any time vary the limits of any such units.

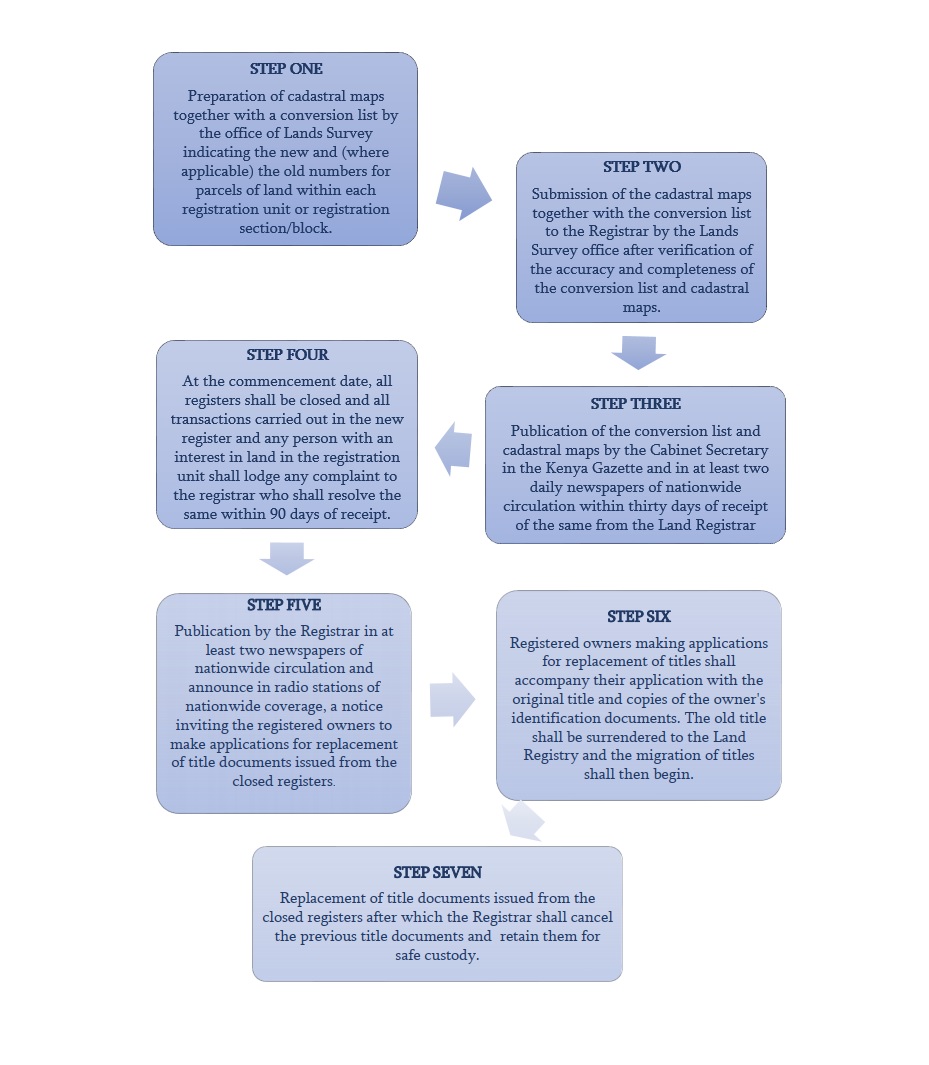

What does the process of conversion entail?

The process of conversion will be undertaken according to the steps outlined in the Regulations as set out below:

Will be there any changes to the size of a property after conversion?

The migration of titles to the new regime shall have no effect on the size and area of a property. This is because conversion shall be done through the use of Registry Index Maps (RIMs) which are generated from survey plans with fixed boundaries. In the event that a landowner wishes to verify the boundaries of their property, the RIMs and survey plans are available at the Survey of Kenya Headquarters for verification.

What effect shall the conversion have on existing interests to the property?

All interests that had been registered against the property at the time of conversion shall be retained in the new register. However, the replacement titles issued shall differ in form from the previous titles.

What if the title to the property subject to conversion is in possession of third parties?

According to the Press Statement issued by the Cabinet Secretary, landowners whose titles are held by financial institutions and other third parties as collateral will have to consult with them on the procedures for release of the titles for purposes of making their application for the title replacement.

When does the process take effect?

The Special Gazette Notice issued contains the list of the parcel numbers which are subject to the conversion process which takes effect on 1st April, 2021.

What steps should you take?

We at AGO Advocates LLP are committed to ensuring our Clients’ rights to property are protected and we advise our esteemed Clients with parcels of land within Nairobi to review the gazette notice which is accessible through this link http://kenyalaw.org/kenya_gazette/gazette/volume/MjI2OA–/Vol.CXXII-No.242/ to confirm the details of their property before the 1st of April, 2021.

In the event that you may have any queries or complaints regarding the same, kindly do not hesitate to visit our offices or contact us via (+254) 020-22 11122 /0100 211 122) or (info@agoadvocates.com).

REQUIREMENTS TO MAINTAIN A BENEFICIAL OWNERSHIP REGISTER

Introduction

On 18th November 2020, the Attorney General vide Legal Notice No. 12 of 2020 published the Companies (Beneficial Ownership Information) Regulations, 2020 (the “Regulations”). These Regulations derive from section 93A of the Companies Act, 2015 (“the Act”) which makes it mandatory for companies to keep and lodge with the Registrar of Companies a register of its beneficial owners before the 31st of January, 2021.

The Regulations require companies and other legal entities incorporated in Kenya to take all reasonable steps to gather and maintain adequate, accurate and current information on their “beneficial owners” on a beneficial ownership register as and from October 2020.

This is seen as a move by Kenya to align herself with international standards and requirements set out by the Financial Action Task Force on Money Laundering (FATF) which Kenya belongs to by virtue of its subscription membership to the Eastern and Southern African Anti-Money Laundering Group (ESAAMLG), an associate member of the FATF, whose main purpose is to combat money laundering and terrorism in the region.

Among the main objectives of the ESAAMLG is to implement recommendations by the FATF which ensure that individuals with significant economic interests in a relevant entity can be identified for the purposes of combating terrorist financing, money laundering and corruption.

Who is a Beneficial Owner?

Under the Act, a “beneficial owner” is defined as “the natural person who ultimately owns or controls a legal person or arrangement or the natural person on whose behalf a transaction is conducted, and includes those persons who exercise ultimate effective control over a legal person or arrangement”.

A beneficial owner of a business is therefore a natural person who meets any of the following conditions in relation to a company:

- holds at least 10% of the issued shares either directly or indirectly,

- exercise at least 10% of the voting rights in the company either directly or indirectly,

- holds a right, either directly or indirectly, to appoint or remove the director of the company, or

- exercises significant control directly or indirectly on the company.

What are the requirements?

With effect from October 2020, companies must create an internal register of their beneficial owners. The Regulations further require companies within 30 days of incorporation, to lodge the list of Beneficial owners with the Registrar of companies. In the event of amendments to the register, the time frame given is 14 days to effect the changes. However, these timelines do not apply to publicly listed companies.

In an instance where the beneficial owners are not known, the company must take “all reasonable steps” to ensure the beneficial ownership information is gathered and recorded on the beneficial ownership register.

Further, in the event that no beneficial owners can be identified, a company may enter the names of the directors of the relevant entity on the beneficial ownership register as the “beneficial owners”.

The register of beneficial ownership must contain the following information in respect of each beneficial owner:

- name, date of birth, nationality and residential address,

- statement of nature and extent of interest held,

- date of entry as a beneficial owner on the register, and

- date of entry of ceasing to be a beneficial owner.

The beneficial ownership register will need to be kept updated whenever there is a change in beneficial ownership, the extent of interest/control or a change in particulars.

It should also be noted that a change in directorship may also trigger an update to the beneficial ownership register, where no beneficial owners have been identified and the directors have been entered in the register as the “beneficial owners”.

Penalties for non-compliance

It is imperative that companies ensure compliance with the Regulations and more so take advantage of the ongoing grace period granted by the Companies Registrar which expires on 31st January, 2021.

It should also be noted that failure by a relevant entity to comply with any of the above obligations is a criminal offence and on conviction each liable to a fine not exceeding Kenya Shillings five hundred thousand (KES 500,000/-). If following conviction, the company remains non-compliant, the company and each of its officers in default commits a further offence on each day of which the failure continues and on conviction are liable to a fine not exceeding Kenya Shillings fifty thousand (KES 50,000/-) for each such offence.

Conclusion

If successfully implemented, the regulations would see tax evasion, money laundering and eventually corruption in both the public and private sectors significantly decline. This is because uncovering and fighting illicit financial flows requires information on who owns, controls or ultimately benefits from any business involved in potentially illegal activities: namely, the beneficial owners. Having this information readily accessible would assist authorities in investigations and prosecutions against financial crimes.

How we can help

At AGO Advocates LLP, we are committed to ensuring all our corporate clients comply with all legal and regulatory requirements. In regard to the Companies (Beneficial Ownership Information) Regulations, 2020, our services include the creation and maintenance of the Beneficial Owners Register as well as identifying and giving notice to the beneficial owners to provide the details required by the Regulations.

Get in touch for any inquiry via (+254) 020-22 11122 /0100 211 122 or (info@agoadvocates.com)

ANALYSIS OF THE BUSINESS LAWS (AMENDMENT) ACT NO. 1 OF 2020

Introduction

The Government has through the recently enacted Business Laws (Amendment) Act, Number 1 of 2020 amended various Statutes to facilitate the ease of doing business in Kenya. The Amendment Act that came into force on the 18th of March 2020 amended sixteen (16) pieces of legislation. The Act has digitalized different processes of transacting including expanding the use of electronic signatures, and removing certain legal requirements that usually delay some transactions.

Although the Government had introduced e-Government services in most of its departments and ministries, it had not comprehensively provided for the use of electronic signatures. The amendment Act has broadened the use of electronic signatures as captured under the different amended statutes, and digitalized legal processes in the Country. The use of advanced electronic signature and electronic signature had been provided for under the Kenya Information and Communication Act, No.1 of 1998 (hereinafter KICA). The definitions of advanced electronic signature and electronic signature are adopted as provided for under the KICA as follows:

“advanced electronic signature “means an electronic signature which is:

- uniquely linked to the signatory;

- capable of identifying the signatory;

- created using means that the signatory may maintain under his or her sole control; and linked to the data to which it relates in such a manner that any subsequent change to the data may be detectable.

“electronic signature” means data in electronic form affixed to or logically associated with other electronic data which may be used to identify the signatory in relation to the data message and indicate the signatory’s approval of the information contained in the data message.

We have summarized the major changes to the specific statutes as below:

- The Law of Contract Act (Cap23 Laws of Kenya)

- Section 3(6) of the law of Contract Act has been amended in the definition of the word “sign”, to incorporate advanced electronic signature. The definition section of the Act now includes the definition of advanced electronic signature.

- The Registration of Documents Act (Cap 285 Laws of Kenya)

- The definitions of “signature” and “signed” have been expanded under the Act to include advanced electronic signature and electronic signature. This is a departure from the previous ways of execution which involved physically appending a mark on the document.

- The definition of “book” now includes an electronic book.

- The Act provides for the Registrar to establish and maintain principal registries at Nairobi and coastal registries at Mombasa in electronic form for ease of online transactions.

- Parties to transactions can now file their documents in physical or electronic form.

- The Survey Act (Cap 299 Laws of Kenya)

- Advanced electronic signature and electronic signature are defined under the definition section of the Act.

- The definition of “signature” under the Act now includes advanced electronic signature and electronic signature.

- Surveyors can now process a document or plan electronically. Such electronically processed document or plan that bears prescribed security feature is deemed to bear the imprint of the seal of the Survey of Kenya. This therefore means that :

- The seal of the Survey of Kenya can now be processed electronically and bear the prescribed security feature.

- Surveyors now have an option to execute documents digitally, and the Director can now authenticate same documents electronically.

- Survey process can now be done electronically by parties that require such services.

- The Stamp duty Act (Cap 280 Laws of Kenya)

- Section 2 of the Stamp Duty Act is amended by deleting the definition of “stamp” and substituting with a definition that includes a mark embossed or impressed by an electronic means.

- Section 119 of the Act is amended to provide for electronic stamping.

The electronic stamping will greatly ease the stamping process and save time for transacting parties.

- The Land Registration Act, No. 3 of 2012

- The definition of Instrument has been expanded to include both physical and electronic form.

- The definitions of advanced electronic signature and electronic signature have now been adopted under the Land Registration Act as defined under KICA.

- The definition of “signature” now includes electronic signature.

- Sections 38 and 39 of the Land Registration Act have been repealed. It is therefore no longer a requirement to produce land rates clearance certificates and land rent clearance certificates to effect registration of an instrument purporting to transfer or create an interest in land. The requirement to obtain consent from the County Land Management Board provided for under section 39(2) of the Act before the registration of any transaction has also been abolished. This however is only applicable to leasehold properties and not freeholds.

- Section 44 (3) (A) is introduced to provide that a document processed and executed by a way of an advance electronic signature or electronic signature by a party consenting to it, is deemed to be a validly executed document.

- Section 45(3) of the Act is amended to provide for electronic processing and execution of documents, provided the parties to the transaction consented to such processing and execution.

- Section 83 of the Act has been amended to give an avenue to persons claiming indemnity to make an application to the Chief Land Registrar for investigation and consideration, and appeal to the high court if aggrieved by the decision of the Chief Land Registrar.

- The Companies Act, No. 17 of 2015

- The requirement of affixing company seal in execution of company documents, contracts and deeds has been removed. These documents are deemed validly executed by a company if it is executed by two (2) authorized signatories or a director of the company in presence of a witness who attests the signature.

- Bearer shares are no longer to be used. This are unregistered equity securities owned by the possessor of physical share documents. Their use had been abolished under the companies Act 2015 due to the increased cost and insecurity associated with it. The bearer shares issued under the previous law will be converted into registered shares within nine (9) months of law coming into effect.

- It is now hard to kick out the minority shareholders following the amendment to section 611 of Companies Act, 2015. The amendment seeks to adopt 90% ‘squeeze-out’ and ‘squeeze-in’ threshold relating to compulsory acquisition of minority stakes in the companies rather than the former 50%. The Former 50% made it easy for the majority shareholders who can easily account for the threshold to force out any minority shareholder(s) who decline to sell their shares, by enforcing squeeze in Through the amendment, Kenya has followed the global practice of holding the threshold at 90% thereby protecting the minority shareholders. This is also in tandem with The Capital Markets (Take-Overs and Mergers) Regulations, 2002, which pursuant to an offer to acquire all shares in a target, an offeror who acquires 90% of the shares and voting rights to which the offer relates, may exercise its statutory rights to acquire compulsorily the remaining shareholders, effectively compelling such shareholders, who may not have accepted the offer to sell their shares to it.

- The Insolvency Act, No.18 of 2015

- The creditors are given the right to request for information regarding a company that has been placed under administration from a relevant Insolvency practitioner. The Insolvency Practitioner shall provide the requested information within five (5) working days or such longer period as agreed between the creditor and the Insolvency practitioner. Extension of the period can only be done upon issuing a written notice to the creditor. Such a notice shall specify the period within which the information can be provided and the reasons for the extension.

- Section 560A of the Act is amended to provide for additional considerations that the court or administrator may take into account on application for approval to lift a moratorium. The additional considerations include:

- Whether the value of the secured creditor’s claim exceeds the value of the encumbered asset;

- Whether the secured creditor is not receiving protection for the diminution in the value of the encumbered asset;

- Whether the provision of the protection is feasible or cumbersome on the estate;

- Whether the encumbered asset is not needed in reorganization or sale of the company as a going concern.

- The Kenya Information and Communications Act, No. 2 of 1998

This Act has been amended at section 83B (1) by deleting paragraph c that restricted the use of electronic signatures to sign documents of title. The restriction however still applies to wills and negotiable instruments.

Conclusion

The amendments are forward looking especially because the world has moved towards the digitalization of transactions, which has been very effective in different parts of the world. Transactions can now be done easily, faster and cost effectively. Also, transactions have been made less bulky due to limited paperwork involved. Further, the changes as captured under the Companies Act and Insolvency Act protect the rights of minority shareholders and unsecured creditors, respectively.

DIGITIZATION OF LAND TRANSACTIONS

The Ministry of Lands and Physical Planning has upgraded the Electronic Management System to ease the processing of Land Transactions at the Ministry.

Late last year, a Public Notice was issued informing land owners within Nairobi and Central Registries that from 4th December 2017 all fees and duties would be paid online within the e-citizen portal. This was effectuated from the said date. The Ministry further issued a Public Notice informing landowners that from 13th April 2018, the following services shall ONLY be available online:

- Application for Registration ( Transfer, Charge, Lease, Caution/Caveat, Court Orders and any other services as may be communicated from time to time)

- Issuance of Consent to Transfer, Charge, Lease etc. will be created automatically upon application

- Valuation requests will be created automatically upon application for Transfer;

- Payment of Land Rent and Issuance of Land Rent Clearance Certificate

- All payments (Payment of Stamp Duty, Registration Fees, Consent Fees)

- Application for official searches (Nairobi and Central Registries – Nairobi Properties)

Target Group

The Land Information Management System targets all land owners and potential investors in land within the Republic of Kenya. Operations of the online platform commenced in the Nairobi and Central Registry with Land Owners within Nairobi being given up to 13th April 2018 to finalize pending manual transactions. The Ministry is working to effect the same in other registries within the Republic of Kenya.

How to Transfer Property Online

As from 13th April 2018, all property owners within Nairobi and Central Registry shall have their land details listed in their profile under ‘Manage Property’ menu in the LIMS via the e citizen portal. The owner shall be required to verify and authenticate their Tittle by uploading a copy of the Tittle and the Transfer Document. Once the Land details are approved at the registry, the proprietor shall be able to access it under ‘Manage Property’ and make an application against it.

For purposes of effecting the Transfer, the Land Owner should scan the following documents to the LIMS portal; Copy of Tittle, County Clearance Certificate, Transfer Instrument ( drawn by an Advocate), Land Control Board Consent ( For Agricultural land only) Land sketch Map for valuation visit, Proof of Occupation ( For New Grants only).

Once the application for registration is submitted online, the original instrument and Tittle Document thereof, shall upon payment of Stamp duty where applicable, be presented at the Land registry for registration.

Properties with active encumbrances (charges, Leases and subleases), inhibitions (court order, restrictions and caveat/cautions are not transferable. This will require application for their removal separately.

All other requirements for transfer e.g. consent approval, valuation of land, stamp duty assessment are already automated and need to be applied separately.

What are the Benefits of Land Information Management System?

- The online land transaction system eliminates the cost associated with keeping of manual records and reduces unnecessary costs associated with land transactions.

- Digitization saves valuable time as it eradicates bureaucracy of the manual system while making payments and processing of land rent and land rates clearances, stamp duty as well as other routine administrative processes.

- With regard to record keeping, the online platform is effective as it minimizes any chances of lost files or fraudulent manipulation of records.

What are the setbacks associated with the Online Platform?

No legal framework for E- Conveyancing

The Land Act No 6 of 2012 and the Land Registration Act No 3 of 2012 came into operation prior to the digitization process therefore failing to regulate electronic conveyancing. There is need for legal and regulatory reforms that will enable the successful implementation of e-conveyancing platform by protecting and promoting the integrity of the land registry system safeguarding and guaranteeing the sanctity of the every Tittle document.

Lack of Public Participation & Involvement of Key Stakeholders

The Ministry of Lands failed to conduct public participation and involve the Law Society of Kenya, as a key stakeholder in determining the mode and methodology of digitization of land transactions.

Lack of Guidelines to Regulate the Digitization Process

Pursuant a Legal Notice No.278 (Land Registration (General) Regulations, 2017 on electronic registration and conveyancing, the Cabinet Secretary in consultation with the National Land Commission is required to issue Guidelines regulating the procedure to be followed in keeping of the register in an electronic format, applying for information or registration and the procedure to be followed by the registrar relating to the various applications.

Conclusion

Digitization of land transactions in Kenya is a positive transformation that will improve the efficiency of our processes. However, there is need to streamline the legal and regulatory framework and to put in place proper e-conveyancing regulations to ensure that the proprietary rights and interests of Land owners are upheld and the sanctity of Tittle documents is maintained.

)